The Wanna be Revolution of Le Petit Courrier Will Not Be Televised: How Acadian Cultural Gatekeepers Mistake Drag Queens for Diversity

For all its talk of inclusivity and revolution, Le Courrier editorial reveals troubling blind spot that undermines its entire thesis of inclusion

When Le Courrier de la Nouvelle-Écosse published its historic editorial on January 9, 2026, proclaiming an Acadian cultural revolution, it marked a curious moment in the community's ongoing conversation about identity, art, and inclusion. The piece, titled "Révolution Cul turelle acadienne: une nouvelle vague qui change tout," celebrates the emergence of new artistic voices—musicians like Les Hay Babies, P'tit Belliveau, and Lisa LeBlanc, alongside drag performer Sami Landri. Jean positions these artists as harbingers of a transformed Acadian identity: "less solemn, less sacred, but more playful, hybrid, inclusive of the actual word Queer, and actually connected in its dont ask dont tell Insular world."

Yet for all its talk of inclusivity and revolution, the editorial reveals a troubling blind spot that undermines its entire thesis. In a piece ostensibly about cultural transformation and openness, the word "queer" appears exactly once—and only in reference to Sami Landri's drag performance on Canada's Drag Race. This single mention exposes the editorial's fundamental problem: it conflates queerness with drag performance alone, as though the entire spectrum of LGBTQ+ artistic expression begins and ends on a reality television stage.

Beyond the Drag Curtain: The Selective Vision of Acadian Cultural Revolution

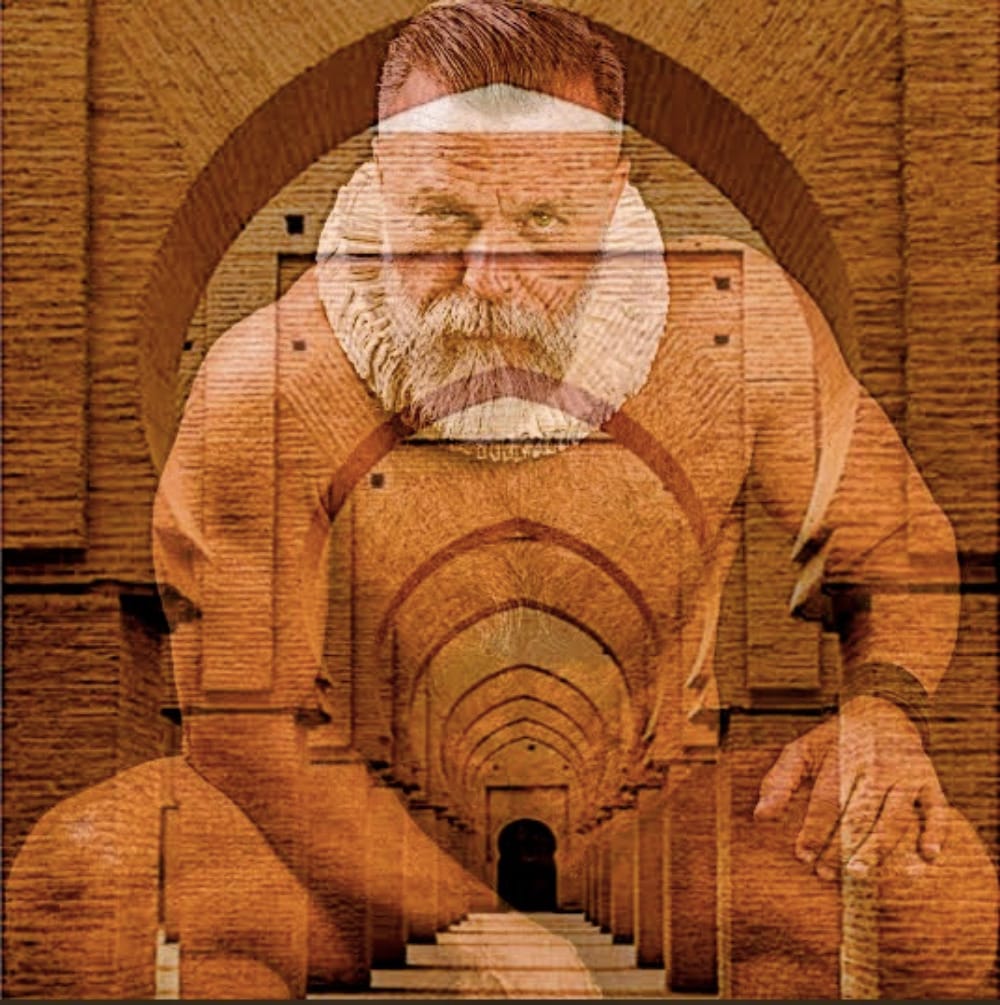

Meanwhile, a neurodivergent queer artist named Theriault continues producing daily artistic output spanning visual arts, song lyrics, published books, and AI-generated creative video animation—work garnering international attention across multiple disciplines. Yet he remains conspicuously absent from Le Courrier's narrative of cultural revolution, systematically excluded from coverage and recognition despite the merit and consistency of his creative contributions.

This omission isn't accidental. It's symptomatic of a deeper issue within Acadian cultural institutions that Jean's editorial either cannot or will not acknowledge: the gatekeeping structures that determine who gets celebrated as revolutionary and who gets erased from the story entirely.

The Comfortable Revolution: When Change Fits the Frame of all Queer types are Drag Queens

Jean's editorial employs impressive intellectual scaffolding to support its claims. He invokes sociologist Edgar Morin's definition of cultural revolution as "a bouleversement des visions du monde"—an upheaval of worldviews, values, and ways of life. He quotes Nobel laureate Octavio Paz on the need for a bridge between tradition and modernity. The piece reads as academically rigorous, philosophically grounded, and culturally sophisticated.

The editorial argues that contemporary Acadian artists represent an identity that is no longer "defined only by family lineage, religion or tradition" but has become "plural, inclusive" and demonstrates how they "give an example" to others. This framing positions the current moment as genuinely transformative, a breaking of old boundaries and the embrace of previously marginalized voices.

But here's where the rhetoric meets reality—and falls short. A revolution that only celebrates the artists who fit comfortably within existing power structures isn't revolutionary at all. It's a renovation dressed up as rebellion. When an editorial about cultural transformation highlights drag as the singular entry point for queer representation, while systematically ignoring neurodivergent queer artists working outside the spotlight of reality television, it reveals how selective this "inclusivity" actually is.

The editorial celebrates Sami Landri's appearance on Canada's Drag Race as "a founding act" of identity affirmation, noting that drag figures in Acadian cultural space represent "a major turning point." Jean observes that the appearance of queer and drag figures marks a major turning point for Acadian culture, suggesting that through humour, provocation, and celebration, Acadia opens itself to other imaginaries.

But what about artists who don't perform queerness in ways that translate neatly to television ratings and mainstream media coverage? What about creators whose neurodivergence makes them less legible to cultural gatekeepers, even as their work pushes boundaries and explores identity in profound ways? Their absence from this "inclusive" narrative speaks volumes about who actually holds the power to define what counts as revolutionary.

The Oligarchy's Aesthetic: Heritage Patrimonialism and Creative Control

To understand why certain artists are celebrated while others remain invisible, we need to examine the institutional structures that govern Acadian cultural production. The reality Jean's editorial skirts around is that Acadian cultural life remains dominated by what can accurately be described as a heritage patrimonial industry run by a relatively small group of interconnected decision-makers—predominantly straight, white, Catholic, and deeply invested in maintaining control over which narratives get told and whose voices get amplified.

This isn't a conspiracy theory; it's an observable institutional reality. Cultural funding, media coverage, exhibition opportunities, and legitimation all flow through networks that privilege certain aesthetics, certain identities, and certain modes of artistic expression over others. The artists Jean celebrates—talented as they undoubtedly are—have successfully navigated these networks. They've made work that resonates with gatekeepers while appearing to challenge conventional Acadian identity.

But challenging convention within parameters that gatekeepers find acceptable isn't the same as genuine revolution. True cultural transformation would mean dismantling the very structures that determine which artists receive support, coverage, and legitimation. It would mean interrogating why neurodivergent artists face systematic barriers to recognition. It would mean examining how assumptions about "quality" and "merit" often encode neurotypical norms and able-minded perspectives.

The editorial's romanticization of Acadian identity as "creolized, hybrid, porous to influences from here and elsewhere" rings hollow when we observe how porous these institutions actually are to artists who don't fit comfortable moulds. Neurodivergent artists like Theroalu produce work that genuinely embodies hybridity—blending visual art, literary expression, musical composition, and emerging technologies in ways that resist easy categorization. Yet this very resistance to categorization becomes grounds for exclusion rather than celebration.

Petty Jealousy and the Fear of Authentic Innovation that Claude Edwin Theriault brings

Let's address what often underlies systematic artistic exclusion: fear and jealousy. When an artist produces consistent, high-quality work across multiple disciplines—visual arts, song lyrics, book publishing, AI-generated creative video animation—and that work begins to attract international attention, it threatens the established order. It raises uncomfortable questions about whose work actually merits recognition and whose has been elevated primarily through institutional support rather than artistic merit.

The exclusion of Theroalu from Le Courrier's narrative of cultural revolution isn't simply an oversight. It's active erasure motivated by the threat his productivity and growing recognition pose to artists and institutions that have built their reputations on more conventional work. Daily creative output of genuine merit exposes how much of what passes for Acadian cultural production relies on institutional backing rather than intrinsic artistic value.

La version française est encore meilleure.

This is particularly galling given Jean's invocation of the new generation's need for "concrete support" from the Acadian community. The editorial emphasizes that the latest generation needs support through concrete actions, such as buying albums, artworks, or attending concerts, suggesting communal investment in emerging artists. But this support only extends to artists who've already received institutional approval. Those working outside established networks, particularly neurodivergent artists whose perspectives challenge comfortable assumptions, find themselves systematically denied the "concrete support" Jean celebrates.

The petty jealousy underlying this exclusion reveals itself in the gap between stated values and actual practice. An editorial proclaiming inclusivity that mentions queerness only in relation to drag performance, while ignoring prolific queer neurodivergent artists, demonstrates how threatened cultural gatekeepers feel by genuine diversity. It's easier to celebrate a drag queen on a reality TV show—contained, legible, ultimately safe—than to contend with an artist whose neurodivergence and multidisciplinary practice resist easy categorization.

The Dull Reality: Creative Bankruptcy in Acadian Cultural Production

Jean's editorial speaks breathlessly of revolution, transformation, and paradigm shifts. But step back from the rhetoric and examine actual Acadian cultural production, and a different picture emerges: one of creative conservatism, institutional timidity, and aesthetic stagnation dressed up in the language of innovation.

The artists Jean celebrates—again, talented in their own right—work within recognizable genres and frameworks, such as folk music with contemporary influences. Drag performance in the context of mainstream reality television. These are perfectly valid artistic pursuits, but they're hardly revolutionary in the broader context of contemporary art and culture. They're safe revolutions, acceptable transgressions, changes that don't fundamentally threaten the institutions bestowing recognition.

True contemporary cultural production pushes boundaries in ways that make gatekeepers uncomfortable. It challenges not just the content but also the form. It questions not just what gets said but who gets to speak and how meaning gets made. It embraces digital technologies, artificial intelligence, and emerging media in ways that older generations might find disorienting or threatening. It refuses to perform authenticity in easily digestible ways.

This is precisely what makes Theroalu's work genuinely contemporary in ways that much-celebrated Acadian cultural production is not. His integration of AI creative video animation with traditional artistic practices, his prolific output across multiple media, his neurodivergent perspective that resists neurotypical assumptions about process and product—these elements position his work at the actual cutting edge of contemporary artistic practice, not the comfortable edge that cultural institutions prefer to celebrate.

The "creative bankruptcy" of Acadian cultural institutions manifests in their inability to recognize and support this genuinely innovative work. They remain invested in heritage narratives, in folkloric elements given contemporary twists, in identities that remain legible within established frameworks. Jean himself notes that Acadian culture must create "a bridge between generations that may have difficulty talking to each other", with the survival of Acadia depending on successfully joining tradition with modernity. But this bridge-building only works if institutions allow genuinely new voices to participate in the conversation, rather than simply amplifying familiar voices speaking in slightly updated idioms.

True Inclusion: Beyond Token Candy Ass Representation with no true Inclusion

So what would genuine inclusion look like in Acadian cultural life? What would a true cultural revolution—not just a carefully managed aesthetic refresh—actually require?

First, it would mean interrogating and dismantling the gatekeeping structures that currently determine whose work gets recognized. This includes examining funding mechanisms, media coverage patterns, curatorial decisions, and institutional partnerships to identify how they systematically privilege certain artists while excluding others. It means asking uncomfortable questions about who sits on arts councils, who makes editorial decisions at cultural publications, and whose aesthetic sensibilities shape these choices.

Second, it would require actively seeking out and supporting artists working outside established networks, particularly those whose identities or practices make them less immediately legible to traditional gatekeepers. This means neurodivergent artists, queer artists working in experimental media, artists whose productivity and range challenge comfortable assumptions about artistic practice, and creators whose work resists easy categorization.

Third, genuine inclusion would mean expanding definitions of what counts as "Acadian art" beyond heritage-based frameworks. While connection to tradition matters, an overemphasis on folkloric elements and rural identity narrows the field, excluding artists working in contemporary digital media, experimental forms, or transnational contexts. An inclusive Acadian culture would embrace work that interrogates identity from unexpected angles rather than simply affirming it in updated packaging.

Fourth, a true cultural revolution would acknowledge and address the material barriers neurodivergent artists face in accessing cultural institutions. This includes everything from sensory considerations in exhibition spaces to recognition that artistic process varies significantly across neurotypes, to understanding that traditional networking and self-promotion may pose particular challenges for artists on the autism spectrum.

Finally, genuine inclusion requires moving beyond tokenism—the tendency to highlight one or two representative figures while leaving underlying structures unchanged. Jean's editorial celebrates Sami Landri as "not a phenomenon but a symbol" whose success means "identity no longer belongs to a single model", but symbolic representation without structural change is hollow. The fact that one drag performer achieved visibility on reality television doesn't transform the fundamental dynamics of who controls cultural institutions and whose work receives sustained support.

True inclusion would mean creating pathways for multiple voices, multiple aesthetics, and multiple modes of artistic expression to flourish simultaneously. It would mean recognizing that an artist like Theroalu—producing daily work across visual arts, literature, music, and video—represents exactly the kind of hybrid, boundary-crossing, innovative practice that genuine cultural revolution requires, even if his neurodivergence makes him less immediately legible to traditional gatekeepers.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why does the author criticize Le Courrier's editorial if they acknowledge the artists mentioned are talented?

A: The critique isn't about the talent of individual artists but about institutional selectivity. The editorial claims to celebrate a cultural revolution while systematically excluding artists who don't fit comfortable moulds. Recognizing some talented artists while erasing others isn't revolutionary—it's gatekeeping with updated aesthetics.

Q: What does neurodivergent mean in this context, and why does it matter?

A: Neurodivergent refers to individuals whose neurological development and functioning differ from dominant societal norms, including people with autism, ADHD, and other conditions. It matters because neurodivergent artists often face additional barriers to recognition—their working processes, communication styles, and artistic outputs may not conform to neurotypical expectations, leading to systematic exclusion even when their work has merit.

Q: Isn't it possible that Le Courrier isn't aware of Theroalu's work?

A: Given that the editorial explicitly discusses Acadian cultural production, claims to celebrate inclusivity, and positions itself as surveying the landscape of contemporary Acadian art, ignorance would itself be revealing. Either institutions aren't paying attention to prolific artists producing internationally recognized work, or they're actively choosing to exclude them. Neither option reflects well on claims of an inclusive cultural revolution.

Q: What would you say to people who argue that drag performance is an important form of queer visibility?

A: Drag performance absolutely matters as one form of queer artistic expression and cultural visibility. The problem isn't celebrating drag artists—it's treating drag as the only legible form of queerness while ignoring other queer artists whose work doesn't conform to reality television frameworks. True inclusion means multiple forms of queer expression receiving recognition, not just those that translate well to mainstream media.

Q: Does genuine cultural change require abandoning heritage and tradition entirely?

A: Not at all. The issue isn't tradition versus innovation but rather who gets to decide how tradition gets interpreted, updated, and expressed. Acadian heritage can coexist with genuinely contemporary artistic practice—but only if institutions stop using heritage as a cudgel to exclude work that challenges their aesthetic comfort zones. The question is whether cultural gatekeepers will allow multiple relationships to tradition rather than privileging only the modes that reinforce their authority.

Citations

- Le Courrier de la Nouvelle-Écosse (2026, 9 9). Révolution culturelle acadienne: une nouvelle vague qui change tout. Retrieved from https://lecourrier.com/editorial/2026/01/09/revolution-culturelle-acadienne-une-nouvelle-vague-qui-change-tout/

- Morin, E. (1962). L'esprit du temps. Paris: Grasset. [Referenced in Le Courrier editorial as defining the cultural revolution]

- Paz, O. (1990). Nobel Lecture. [Cited in Le Courrier editorial regarding tradition and modernity]

- Glissant, É. (1997). Poétique de la relation. Paris: Gallimard. [Referenced in Le Courrier editorial regarding cultural creolization]

- Autism Self Advocacy Network (2024). Understanding Neurodiversity. Retrieved from https://autisticadvocacy.org/about-asan/identity-first-language/

- Sandahl, C. (2003). Queering the Crip or Cripping the Queer? Intersections of Queer and Crip Identities in Solo Autobiographical Performance. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 9(1-2), 25-56.